EndoAxis Clinical Team

PMS isn’t about hormones being ‘off’ — it’s about how the brain responds to them.

Hormones Are the Trigger, Not the Root Cause

Estrogen and progesterone rise and fall in every cycle. Yet only some women experience PMS. Why? Because PMS is rooted in neurochemical sensitivity, not hormone levels.

Neurotransmitter Systems Are the Real Players

| Serotonin: The Mood Thermostat |

| Estrogen boosts serotonin; progesterone modulates it. In PMS, the brain becomes less responsive to serotonin. This drives: Mood swings, Depression, and Carbohydrate cravings (a self-regulation attempt to raise serotonin).SSRIs often outperform hormone treatments in PMDD — proof it’s about serotonin, not estrogen. |

| Allopregnanolone & GABA: The Paradox of Progesterone |

| Progesterone is converted into allopregnanolone, which should calm the brain via GABA-A receptors. But in PMS/PMDD brains, this has a paradoxical effect — increasing anxiety and irritability. The brain misfires on a signal that should soothe it.It’s not “low progesterone” — it’s a broken feedback loop in the brain’s calming system. |

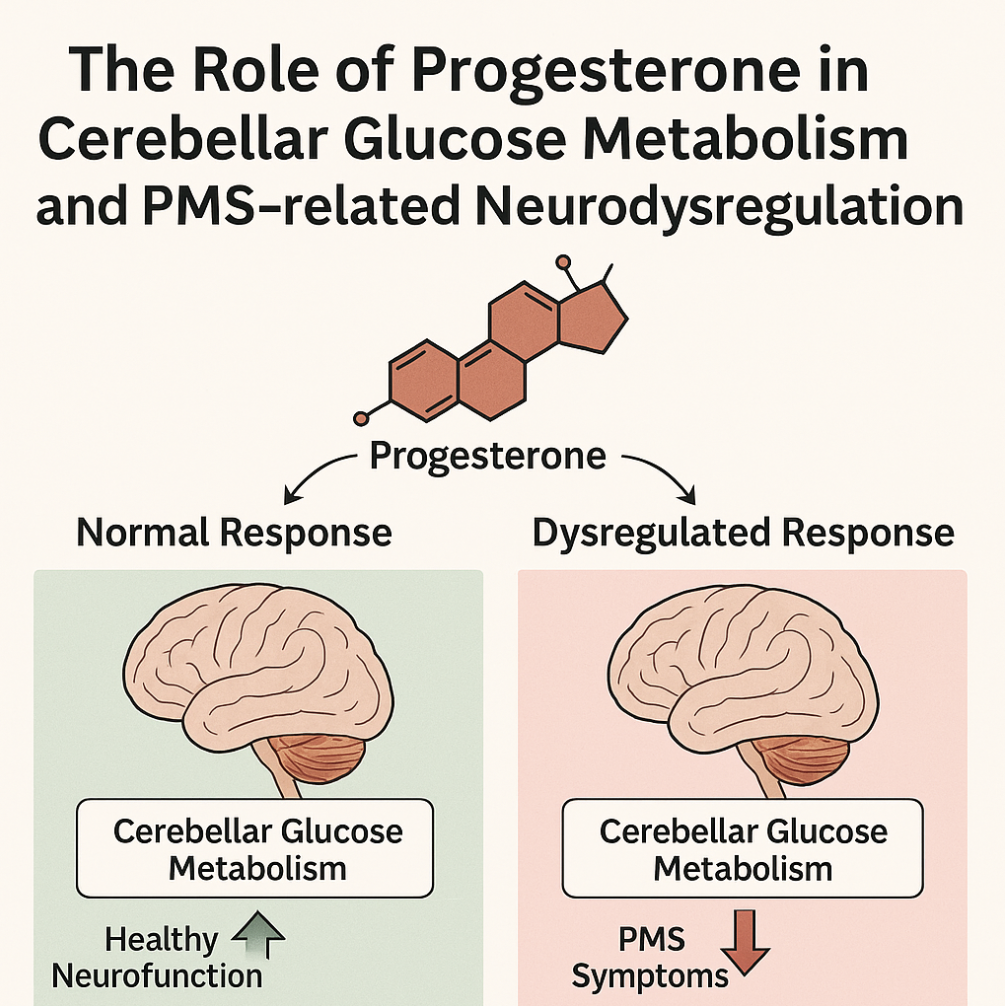

| The Role of Progesterone in Cerebellar Glucose Metabolism and PMS-related Neurodysregulation |

| Progesterone increases metabolic activity in the cerebellum, supporting its role in cognitive, motor, and emotional integration. Increasing evidence points to the cerebellum’s heightened metabolic activity in response to progesterone as a key contributor to both normal cognitive-emotional regulation and the pathophysiology of premenstrual syndrome (PMS)Dysfunction in mitochondrial activity or glucose transport under progesterone influence may . underlie this cerebellar energy deficit. |

However, not all individuals exhibit an adaptive neuroenergetic response to this hormonal shift. In the PMS brain, a dysregulation in glucose utilization by cerebellar neurons has been observed, potentially due to impaired progesterone-mediated mitochondrial signaling or glucose transporter function. When cerebellar glucose metabolism is impaired, the resulting neurofunctional imbalance may trigger a compensatory hyperactivation of other brain regions, notably the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). Overactivation of the PFC and ACC can cause rigid thinking, hyperfixation, and difficulty regulating anxious thoughts—key features of PMS-related cognitive-emotional dysregulation.

Genetic “Mood Imprinting”

Variants in the 5-HTTLPR gene (serotonin transporter) and GABA receptor genes increase risk of PMS. Neuroimaging reveals PMS brains light up differently – especially the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate. This isn’t just a bad mood — it’s a measurable shift in brain function.

A Tale of Two Luteal Phases

Importantly, this divergence in neurocognitive experience during the luteal phase cannot be solely attributed to circulating hormone levels. Women with identical estrogen-to-progesterone ratios may experience drastically different neurological and psychological states. This suggests that individual differences in neuroenergetic responsiveness—particularly cerebellar glucose utilization—are critical to understanding PMS vulnerability.

Key Takeaways

PMS is best understood not as a hormone disorder, but as a neurosteroid sensitivity syndrome — where the brain misinterprets hormonal messages.

Supporting the Sensitive Brain: a Nutritional Strategy

Understanding PMS/PMDD as a neurosteroid sensitivity disorder opens the door to more intelligent, upstream support – not by blocking hormones, but by buffering the brain’s stress and neurotransmitter systems.