EndoAxis Clinical Team

In our prior discussion, we examined cortisol and its physiological effects on the cortisol awakening response (CAR). You can reference that overview here:

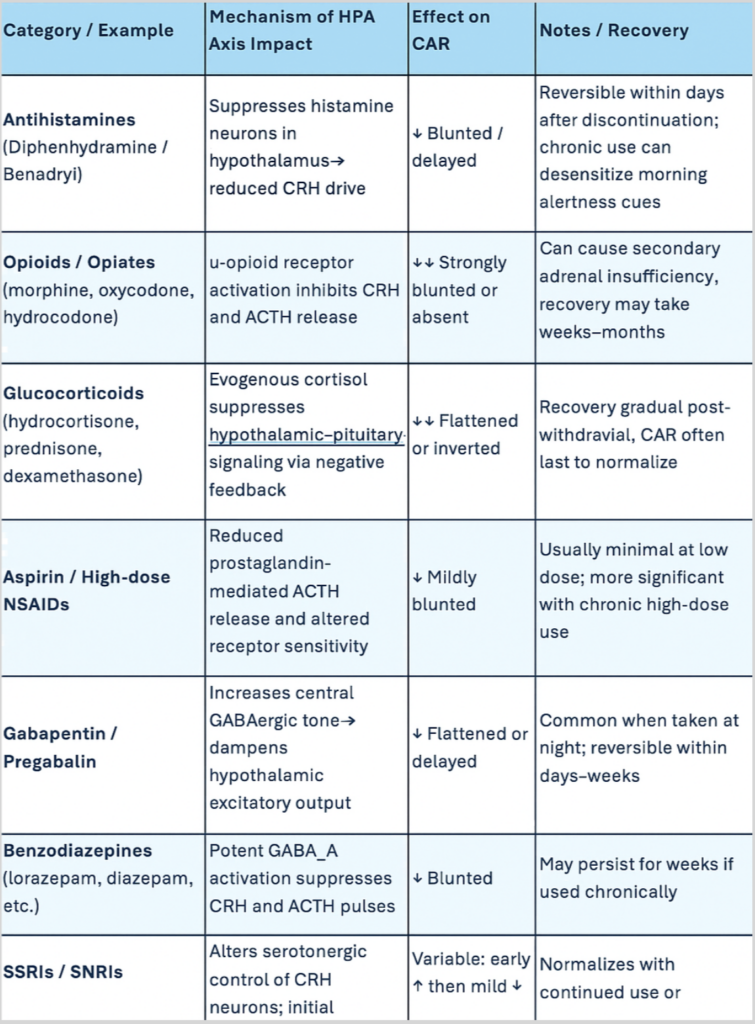

This segment will address how various medications may impact the CAR, allowing for a more nuanced interpretation of results in the context of pharmacologic influences.

The cortisol awakening response (CAR) is a remarkably sensitive reflection of how well the brain and adrenal system communicate at the start of each day.

The CAR represents how well our HPA Axis is responding.

Because it’s centrally driven, originating from hypothalamic and pituitary signaling rather than adrenal capacity alone, it’s easily disrupted by medications and substances that act on the brain, endocrine system, or circadian machinery.

When we see a flattened or delayed CAR on something like a DUTCH test, certain medications can be important culprits.

Medications & Their Impacts

Antihistamines (Diphenhydramine / Benadryl)

Starting with antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), these agents cross the blood–brain barrier and suppress histamine signaling in the hypothalamus.

Since histamine neurons play a role in promoting wakefulness and stimulating CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone) secretion, their inhibition tends to quiet the early-morning activation of the HPA axis.

The result is often a muted cortisol rise, especially in people using these medications at night to aid sleep.

Over time, that sedation can create not only morning grogginess but also an objectively blunted CAR pattern, as the hypothalamus receives weaker wake-up cues.

Opioids / Opiates (morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone)

Opioids have a more direct and pronounced effect. They strongly inhibit CRH and ACTH release through µ-opioid receptor activation in the hypothalamus and pituitary, effectively putting a brake on the entire HPA axis.

Chronic opioid use can lead to secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency: where the adrenals are intact but under-stimulated.

In these cases, CAR is often almost completely absent, and patients experience the classic triad of low morning energy, poor stress tolerance, and sometimes low sodium or blood pressure.

Even short-acting opioids can blunt the CAR temporarily if used regularly, though the suppression tends to be reversible after withdrawal.

Glucocorticoids (hydrocortisone, prednisone, dexamethasone)

The picture is similar with glucocorticoids such as hydrocortisone, prednisone, or dexamethasone.

These drugs provide exogenous cortisol or cortisol analogues, which feed back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to suppress ACTH secretion.

The timing of dosing matters: morning administration can mask the natural cortisol peak, while evening dosing can flatten or even invert the next day’s CAR.

Chronic steroid use, even at physiologic replacement doses, can suppress endogenous production for weeks or months after cessation, and recovery of the CAR is often one of the last rhythmic features to normalize.

Aspirin / High-dose NSAIDs

Aspirin and other NSAIDs can also influence cortisol rhythms, though usually more subtly.

At higher doses — around one gram per day or more — aspirin reduces prostaglandin E₂ signaling, which in turn blunts ACTH release. It can also alter glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity.

While low-dose aspirin (like 81 mg daily) rarely has a meaningful impact, chronic or high-dose use has been shown in research settings to reduce overall cortisol output during the morning window.

This is one reason high-dose NSAID therapy can occasionally contribute to fatigue or muted stress reactivity.

Gabapentin / Pregabalin

Gabapentin, and related drugs such as pregabalin, act indirectly through GABAergic pathways, increasing inhibitory tone in the brain.

Though they don’t bind directly to GABA receptors, their net effect is to calm neuronal excitability, including in the hypothalamus.

Because the early-morning cortisol surge depends on excitatory signaling to initiate CRH and ACTH pulses, this pharmacologic quieting tends to flatten or delay the CAR.

People taking gabapentin for sleep or neuropathic pain often feel groggy on waking, mirroring what’s happening hormonally.

Benzodiazepines and Alcohol

The same general principle extends to benzodiazepines and alcohol, which both heighten GABAergic inhibition and suppress nocturnal ACTH release, leading to a diminished morning cortisol spike.

Beta-blockers

Beta-blockers blunt sympathetic activation, subtly flattening the CAR as well.

SSRIs / SNRIs

On the other hand, SSRIs and SNRIs can have variable effects: they may initially elevate cortisol output, then normalize or mildly reduce it with chronic use, depending on dose and individual neuroendocrine sensitivity.

Mechanistic Summary

Altogether, these substances share a mechanistic theme: interference with the hypothalamic–pituitary signaling that drives the cortisol surge.

Whether by dampening CRH release, suppressing ACTH secretion, or providing negative feedback through exogenous hormones, they disconnect the central clock from adrenal responsiveness.

Fortunately, for most of these, the effect is reversible once the drug is discontinued — though the recovery timeline can range from a few days (for antihistamines or alcohol) to several months (for opioids or steroids), depending on duration of exposure.

Medication & Substance Effects on Cortisol Awakening Response

*Bonus Graph!